Wildfires are the kind of disaster no one is ever fully prepared for. They move fast, destroy without warning, and leave behind questions that don’t disappear once the flames are gone. Even after the smoke clears, people are left wondering what’s safe, what’s changed, and which parts of everyday life have been quietly affected.

One of the first things that comes into question is water. Can it still be used? Is it safe to drink, cook with, or even shower in? And when officials say the water is “back to normal,” it’s hard not to ask what normal actually means.

In Los Angeles, these questions became very real after recent wildfires. Bottled water was distributed, restrictions were announced, and many residents noticed that their tap water simply didn’t feel the same. While the damage above ground was visible, what was happening inside LA’s water system was far less obvious.

To get clearer, fact-based answers, I spoke with Johnny H.Pujol, CEO of SimpleLab, a company that conducts residential water testing across the U.S., including extensive post-wildfire testing in Los Angeles through their Tap Score program. His insights help explain what actually happens to water after a wildfire and why LA’s water can feel different long after the fire is out.

What Happens to Water After a Wildfire?

Water systems are designed for resilience, but they are not built to withstand the extreme intensity of a wildfire. As John explained, these fires don’t just consume homes and vegetation, they also inflict severe damage on pipes, storage tanks, hydrants, and pressure systems.

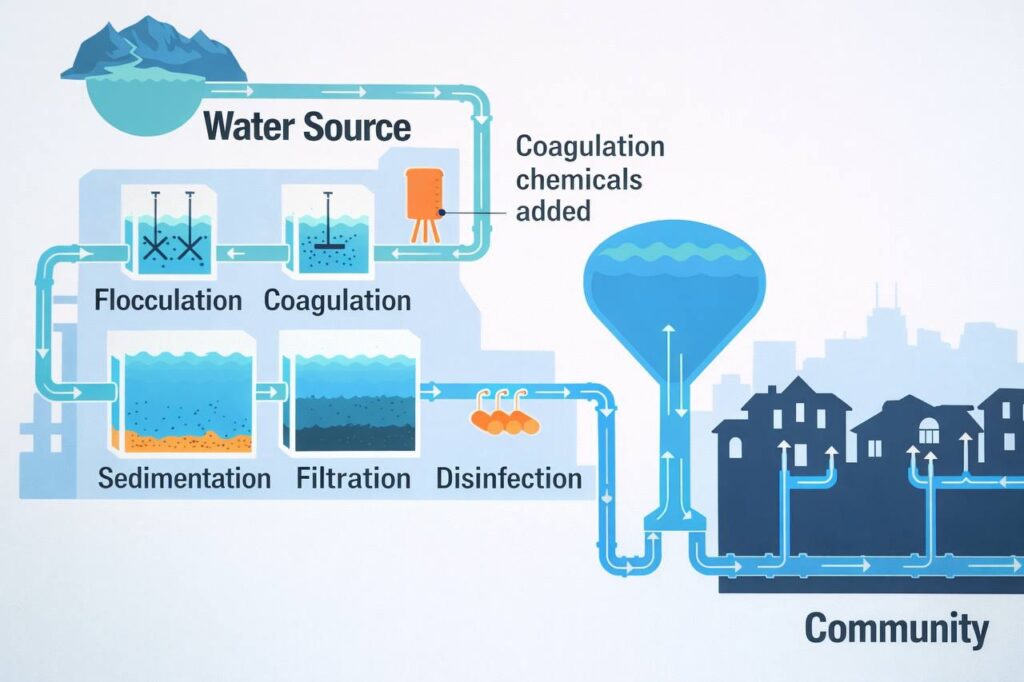

As shown in the diagram, water undergoes an extensive treatment and distribution process. While each treatment plant may differ from the other, we can safely say that the initial water source may be protected, the wildfire’s real threat often lies in the final stages, the storage tanks and the distribution pipes within the community where infrastructure damage can compromise safety.

Once water enters a city’s distribution network, it relies on sealed, pressurized pipes to remain protected. Wildfires put extreme stress on this infrastructure:

- Infrastructure Damage: Intense heat from fire can cause pipes to crack, melt, or split open.

- Loss of Pressure: When the system loses pressure, it creates a vacuum effect. Instead of pushing clean water out, the system can begin to pull contaminants inward from the surrounding environment.

- Burned Materials: Contaminants from ash and burned materials can enter compromised pipes, affecting the water long before it reaches your tap.

Tip: always be skeptical about your water after a fire, call your treatment plant for assurance or install a point of use filter for an additional layer of protection.

How Local Authorities Respond to Water Contamination

According to John, LA’s water utilities acted quickly, shutting down damaged sections, issuing “do not drink” notices, and distributing bottled water. From an operational standpoint, this response was reasonable.

However, water systems in a city like Los Angeles are extremely complex. Different neighborhoods receive water from different sources, through different pipe networks, and not all damage is immediately visible.

John mentioned that utilities often hesitate to communicate too much information too early, simply because they don’t yet have all the answers. This can feel frustrating for residents, but it reflects how difficult it is to assess contamination across a massive urban system in real time.

The City’s Responsibility vs. Your Home Plumbing

One critical point John emphasized is where the city’s responsibility ends: water utilities are responsible for delivering safe water only up to your property line. Everything beyond that, including your building’s internal plumbing, pipes, fixtures, and storage is the responsibility of the homeowner or building owner. So if your home’s pipes were also affected by the fire, that’s one more thing you need to worry about.

After a wildfire, this distinction matters more than ever. Even if the city successfully restores water quality within the main distribution network, contamination can still linger inside individual buildings, particularly older ones.testing is often the only way to understand what’s actually happening in the pipes specific to where you are. By testing your own tap water, you can move beyond general city-wide statements and decide what is safe for you based on real data.

Here is the video where I do a simple test of my tap water at home and break down the results step by step. But in case of fire like this, there is no DIY tester you can do at home. It’s best to either ask a professional or send it to a certified lab right away.

Tip: After a wildfire, always get your own water tested. Don’t just rely on general info or what your neighbors say.

Even if their pipes are fine, yours might not be. It’s safest to consult a professional or send a sample to a certified lab as soon as possible.

How Bacteria and VOCs Spread After a Fire

Wildfires create two major contamination pathways that fundamentally change water chemistry.

1. First, burning materials such as plastic pipes, insulation, fuel, and household chemicals release toxic compounds known as VOCs into the water system.

2. Second, when pipes lose pressure or break, they can suck in soil, ash, and chemical residues from the surrounding environment.

John explained that this combination leads to complex chemical contamination. This calls for an additional layer of distinction for safety.

This is why water quality is measured against EPA standards, which set strict health-based guidelines not only for bacteria but also for chemical concentrations to ensure the water is safe for long-term consumption.

Tip: If your local authorities issue a “Do Not Use” order instead of a “Boil Water” notice, it’s usually because of chemical VOCs. Unlike bacteria, these chemicals cannot be boiled away; in fact, boiling can sometimes release these toxins into the air as harmful vapors.

The Main Water Contaminants After a Wildfire

Based on post-wildfire testing in Los Angeles, John highlighted several contaminants that appeared more frequently after the fires. Many of these are documented by the EPA as significant risks to drinking water systems following a disaster:

- Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs): This group includes chemicals like benzene, toluene, and styrene. These often enter the system when plastic pipes melt or household materials burn.

- Semi-volatile Compounds: This includes PFAS (often called “forever chemicals”) which can be introduced through firefighting foams or the combustion of consumer goods.

- Disinfection Byproducts: These are created when utilities increase chlorination to combat potential bacteria, which can then react with the high levels of organic matter left behind by a fire.

- Heavy Metals: Metals like lead, arsenic, or copper can leach into the water from damaged internal plumbing or burned infrastructure, a concern noted in wildfire recovery guides from the CDC.

These substances often cause distinct chemical or plastic-like smells and tastes, which many LA residents reported even weeks after the fires. Because these contaminants are chemical in nature, they represent a unique risk: standard disinfection methods like boiling are often ineffective, and in some cases, can actually make the water more hazardous by concentrating the chemicals.

Insight: If you notice a “sweet” or “solvent-like” smell in your water, it is a strong indicator of VOCs.

Health Risks: Immediate vs. Long-Term Exposure

John made an important distinction between acute and chronic health risks. To stay safe, it is vital to understand that water safety isn’t just about how you feel today.

- Acute Risks (Immediate): These occur when high concentrations of contaminants enter the system, potentially making you sick right away. These are the risks that trigger emergency warnings and “Do Not Drink” notices from the CDC.

- Chronic Risks (Long-Term): These are slower and more subtle. Contaminants like benzene or arsenic may not cause immediate symptoms, but long-term exposure to VOCs can lead to serious health effects over time, including immune system damage or increased cancer risk.

This is exactly why water that seems “fine” in the short term may still deserve closer attention.

Tip: If you are in a fire-impacted area and your water has a “burnt” or “plastic” odor, do not rely on a standard refrigerator filter or a basic pitcher. Most are designed only for taste and odor (like chlorine) and are not rated to remove the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and heavy metals that follow a wildfire.

Why Filtering Your Tap Water After a Fire Matters

According to John, one of the most effective short-term protections for residents is activated carbon filtration. Because wildfires introduce complex chemical compounds, carbon filters are specifically valued for their ability to adsorb Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) and other wildfire-related contaminants that standard filters might miss.

In some parts of California, utilities have even distributed point-of-use filters to homes when centralized treatment wasn’t immediately possible. Examples of POU filters include 3 stage filters, reverse osmosis or 2in1 options. While bottled water is a common emergency solution, John pointed out that high-quality filtration provides more sustainable, ongoing protection, especially when contamination lingers in your building’s pipes long after the initial crisis has passed.

Integrating a filtration system at home gives you a dedicated safety layer between the city’s distribution network and your glass.

Top 3 Water Concerns in LA Right Now

Based on current data from TapScore & SimpleLab, John identified three key concerns for Los Angeles residents. These issues highlight why generalized statements about “safe water” don’t always tell the full story for every household:

- Chlorine Disinfection Byproducts: When utilities increase chlorine levels to ensure microbial safety after a fire, it can react with organic matter to create byproducts like Trihalomethanes (THMs), which are regulated by the EPA due to long-term health risks.

- Lead and Plumbing-Related Metals: Older infrastructure in many LA neighborhoods remains vulnerable. If a wildfire damages pipes or causes a shift in water chemistry, lead and copper can leach from aged service lines or household fixtures into your drinking water.

- Naturally Occurring Arsenic: In certain areas, LA relies on groundwater which may contain naturally occurring arsenic. Wildfire-driven changes in the water table or extraction patterns can sometimes fluctuate these levels.

These risks vary significantly depending on your specific neighborhood, the age of your building, and the condition of your plumbing. This variability is exactly why a report for your zip code might look perfect, while the water coming out of your specific kitchen faucet tells a different story.

Tip: You can check your local LADWP Annual Water Quality Report to see the “average” levels for your area, but remember that these reports do not account for the lead or contaminants introduced by your home’s own internal plumbing or local pipe breaks.

Final Thoughts

Wildfires don’t end when the flames are extinguished. Their impact on water systems can last weeks, months, or even longer, often in ways that aren’t immediately visible.

Los Angeles handled the immediate response well, but as this interview showed, water safety after a wildfire is layered and complex. Understanding where contamination happens and what you can do at home makes all the difference. Clean water isn’t just about the source; it’s about the journey it takes to reach your tap.

Summary

- Wildfires can damage pipes and cause chemical contamination (VOCs) through depressurization.

- Water may be safe at the city source but can become compromised within the distribution network or your home’s plumbing.

- VOCs and PFAS are common post-wildfire risks that standard disinfection (like chlorine or boiling) cannot remove.

- City utilities don’t control your internal plumbing; testing at the tap and using activated

- carbon filters are your best personal safeguards.

Do’s and Don’ts

Do: Check for specific “Do Not Use” vs. “Boil Water” notices. Local authorities use these terms differently. A “Do Not Use” order means chemicals like benzene are present, and the water is unsafe for any purpose, including bathing.

Don’t: Boil your water if you suspect chemical contamination. While boiling kills bacteria, it actually makes chemicals like VOCs more dangerous by turning them into toxic vapors that you can accidentally inhale.

Do: Flush your entire home system once the water is cleared. Run every cold-water tap for at least 5–10 minutes. This removes stagnant water and ash that may have settled in your service lines while the system was depressurized.

Don’t: Use your dishwasher’s “Heat Dry” setting. During the recovery period, the high heat of a dishwasher can vaporize lingering chemicals into your kitchen’s air. Stick to the air-dry setting until you’ve confirmed your water is chemical-free.

Do: Test your water and consider installing a point-of-use filter (like activated carbon or RO) after a wildfire. This adds an extra layer of protection against wildfire-related chemicals that standard treatment may miss.

Don’t: Assume your home’s plumbing is safe just because city water has been cleared. Internal pipes can hold contaminants longer than the main system, especially VOCs and other wildfire-related compounds that can cling to plastic plumbing and leach out over time.

FAQ

Can I shower with tap water after a wildfire?

If authorities issue a “Do Not Drink” notice, it’s best not to shower with it either. Hot water can cause VOCs to turn into vapor, which creates an inhalation risk. If not, don’t freely assume it’s safe. Get it tested, and then consider showering.

Why does my water smell like plastic or chemicals?

When plastic pipes melt or household materials burn near water lines, they release compounds like benzene and styrene. These can be “sucked” into the system if pressure is lost, leading to distinct chemical odors. So one reason may be due to a fire.

Is boiling water enough to make it safe?

No. Boiling is for killing bacteria. It does not remove chemicals like VOCs or heavy metals. In fact, boiling contaminated water can actually concentrate those chemicals or release them into the air you breathe.

How long does wildfire contamination last?

It varies. Some contaminants are flushed out quickly, but others can “soak” into plastic pipes and leach out slowly over weeks or months. This is why long-term monitoring is often necessary.

What should I do about my water during a wildfire?

During an active wildfire, authorities may shut down or restrict water in affected zones to prevent contamination. If you are in an impacted area, it’s safest to follow official notices and avoid using tap water for drinking or cooking until it’s confirmed safe. Wildfires can damage pipes and cause pressure loss, which can let contamination enter the system. Once conditions stabilize, flushing your pipes and getting your tap tested can help make sure your home’s plumbing wasn’t affected.

What is the best type of filter to have after a wildfire?

After a wildfire, the focus is on removing chemical contaminants rather than just ash or sediment. Filters that use Activated Carbon or Reverse Osmosis (RO) are considered effective because they can reduce VOCs and other chemical compounds associated with burned materials. Basic sediment filters or pitcher filters only handle dirt or taste—they do not typically address wildfire-related chemicals.

Can I drink from my home filter after a wildfire?

Not immediately. Even high-quality filters can become overwhelmed if the pipes in your home were exposed to contaminated water during the fire or a pressure loss event. Before relying on your home filter, it’s safest to flush your lines, replace the filter cartridges, and if possible, test your tap. Until then, follow local guidance or use bottled water.